Tod Dockstader’s second Starkland CD begins with the composer’s pulsing, spatially-shifting Traveling Music. He explains some background:

“Traveling Music was originally composed as a monaural piece (Electronic Piece No. 8). It was, in effect, my Poeme Electronique, after Varese, and my first piece to be strictly organized with a few sound-materials (instead of throwing everything in and stirring briskly, as I’d done prior to this). When I got the use of a two-track recorder, I used this piece, instead of doing a new work, so I could concentrate on teaching myself the techniques of placing sound in space (between speakers) and moving it through space – hence the title. (Jackie Gleason, in his black-and-white TV days, used always to ask the pit-band conductor for ‘a little traveling music’ to help him move across the stage.)”

Dockstader writes:

“Luna Park was my first ‘new’ piece in stereo. I used some of the techniques I’d learned doing Traveling Music: tape-echo antiphony, delay between channels, placement, and ‘panning.’ By now, the organization of the sounds was very important to me: Luna is a very simple piece: three movements – fast/slow/fast – using few sound-materials. (People remember the laughter; one station broadcast it as ‘Dockstader’s Laughing Music’ – but there actually isn’t that much laughter in it.) I wanted it to be silly and sad and simple. The title comes from the old Luna Park at Coney Island, named for Miss Luna Dundy of Des Moines, sister of one of the park’s founders. The park burned down in the 1940s, and, by the time I saw it, all that remained was a vast, rutted parking lot.

The CD’s major work is the brooding, ominous Apocalypse. The composer details the disparate elements of this four-part masterpiece:

“Apocalypse followed Luna: I wanted to do something heavier, thicker in texture, more unruly and alarming – a concrete Dies Irae. The slowed (creaking) doors and the cat-cry toy are central to it: they provided the threat and despair I wanted. (The cat-cry toy was a little round box with a picture of a cat on it which, when you turned it upside-down, emitted a thin, pathetic little cry – slowed [on tape], it became, I thought, heart-wrenching.) The passage of Gregorian chant, in Part Two, was used as a vocalization of the door sounds – I’m always looking for sounds of different timbres that express the same emotion. The inclusion of Hitler (tape-echoed into gibberish) in the last part is from my Radio childhood, when I heard his broadcasts in the late thirties: I didn’t understand a word, but the terrifying sound of it (made stranger by the shortwave phasing) stayed with me. The sonic boom(s) were almost the only sound I had that had been originally recorded in stereo: the sound-materials in all my work were, originally, almost all monaural, recorded all over the place in a time before portable stereo tape recorders. (The ‘live’ cat in Part Four sang one night outside our apartment window in the Village: I hung a mic out the window for most of the night, recording his arias.)”

Dockstader’s extensive work creating Apocalypse generated additional worthwhile material that premiered on this Starkland CD. He explains:

“Two Fragments from Apocalypse like the Two Moons of Quatermass,were ‘thrown out’ from the main work as it cooled and contracted (over a period of months of editing the mixes). Most ‘outs’ end up on the floor, inankle-deep snarls of tape, and, at the end of the day, are gathered to TheLord (in a wastebasket). But, sometimes, whole blocks have to come out, because, though they’re good, they’re hurting the forward motion of the piece: they’re Digressions (I digress a lot, because I push in a lot of directionswhen I’m making a piece – of music or of writing). But, in these cases, I save them, and after the main work is complete, go back and see if they can stand alone as pieces, themselves. So I hack away at them, and sometimes they just vanish: the razor blade reduces them into nothing – which tells me they weren’t Pieces in the first place. These two held up under the Blade.”

The divergently moody Drone has this history:

“Drone started one way and went another way (like the Telemetry Tapes did, three years later). I had collected recordings of racing cars in motion, because I liked the droning sound they made, the Doppler-effect of pitch-change (without timbral change) as they passed the microphone. To find an equivalent sound that would be ‘playable’ – more controllable – I recorded a lot of sustained tones on an acoustic guitar, ‘Dopplering’ them with tape-speed changes. But, in use, it all became, for me, boring. It was the sort of sound that later became the material for minimalist music, and I wanted maximist music. So, in the process of working on it, the cars just drove away, though some of the guitar survived, along with the title. The musicalimpetus for the piece was Japanese court music, Gagaku, which I’d heard a lot of, and liked. I tried to combine that kind of sound with some violence – the violence I felt that was lurking, almost unheard, under the restraints of Gagaku. So the piece goes back and forth between drone and demolition, a kind of desert demolition-derby.”

The CD concludes with the premiere recordings of Dockstader’s last “organized sound” music. He writes:

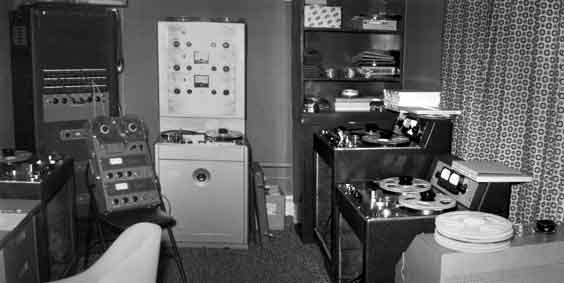

“Four Telemetry Tapes are the last pieces of true organized sound I did – though they’re almost entirely ‘electronic’: three rewired audio test generators, played by twisting dials and knobs. The original idea came from recordings of early satellites, starting with Sputnik: the messages they sent back to earth, ‘telemetry,’ were, to my ears, in the form of loops, slowly and subtly changing over transmission times. I constructed a lot of these loops, and started to mix them – and managed to create an early form of what became New Age music: restful, but, to me, dull. So, as I had with Drone, I threw out the score (but kept the title) and began to improvise, trying to find out how far I could push those three generators. The loops would have been much easier, as it turned out: almost every note had to be cut into shape, on tape: attacks, sustains, decays – my ‘envelopes’ were handmade with a razor blade and a steel straight-edge, and so much splicing tape that the original tape is often entirely white. The tapes were finished just about the time that the first ‘personal’ synthesizers became available, along with sequencers – and all that work was instantly made obsolete. But it was fun to do, fun to push those primitive means so far into what became the immediate future.

Tod Dockstader’s musique concrete turns out to have a surprising relevance to music created decades later; he’s been described as “one of the godfathers of Nurse With Wound, and a distant cousin of rap and techno” (Option). Craig Anderton writes that Dockstader was one of the few to master “the art of assembling tape-recorded sounds and painstakingly splicing, cutting, dubbing, manipulating and mixing to create final compositions,” then adds: “If you think that sounds similar to the procedures used to create today’s cutting-edge pop music, you’re right.”

Tod Dockstader more comments

I don’t remember just when I first heard musique concrète; it must have been in the early ’50s. I think I liked the idea of it more than the Toonerville-Trolley sound of the early pieces.

In Pierre Schaeffer’s original definition, it meant working with the sound in your ears, directly with the sound, as opposed to “abstract” music in which the sounds are written. Like Schaeffer, a working sound engineer, I had the training to be a “worker in rhythms, frequencies, and intensities.”

In the beginning, musique concrète wasn’t even agreed upon to be music; Schaeffer’s first presentation of his work was called “a concert of noises.”

Any art is, of course, not just all the possibilities; it is also choice – organization. That this new sound-art could be rigorously organized I first learned by hearing Edgard Varèse’s Poème électronique of 1958 – a powerfully dramatic work in which the strength and personality of choice among all the possibilities is very evident. My choice of the term “Organized Sound” for my own work was, in part, a tribute to the Poème and to Varèse.

Tod Dockstader

As an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota, Dockstader majored in psychology and art. Then, as a graduate student, he went on to study painting and film, paying his way by doing cartoons for local newspapers and magazines.

In 1955, Dockstader headed for Hollywood. For his first job there as an apprentice film editor, he cut picture and sound for animated cartoons, including “Mr. Magoo” and “Gerald McBoing-Boing.” He moved on to writing and storyboarding cartoons, where his greatest creation was “The FreezeYum Story,” about a Good Humor salesman who turned his ice-cream truck into a sonic spectacular, and got himself fired for his dreams. Truth following fiction, Dockstader was then laid off when the studio folded, and he moved to New York.

Becoming a self-taught sound engineer and sound effects specialist, in 1958 he apprenticed as a recording engineer at Gotham Recording. At this major commercial studio, Dockstader surreptitiously used off-work hours to collect interesting sounds and to experiment with musique concrète.

In the mid 1960s Owl Records released three albums of Dockstader’s music, which led to favorable reviews in such publications as Saturday Review, Audio and High Fidelity.

Around this time of his new national recognition, Dockstader, being an outsider without academic credentials, was denied grants and access to the major electronic music centers. (The Columbia-Princeton Center turned him away.)

In the early 1980s, interest in Dockstader was further stimulated by some highly enthusiastic reviews of the Owl recordings in alternative publications like OP, Recordings of Experimental Music, and Surface Noise.

Released in the early 1990s, Starkland’s two Dockstader CDs brought steadily increasing recognition to this pioneering composer. These CDs elicited further acclaim, from international alternative music publications like the UK’s The Wire (which praised both the music and the “obsessive care” used to produce these CDs) to mainstream US publications like The Washington Post and Stereophile (which places Dockstader alongside Varèse, Stockhausen, and Subotnick in the area of electronic music). Reinvigorated, Dockstader returned to music at the start of the 21st century, adopting computer composition in favor of tapes. New CDs appeared from Sub Rosa and ReR Megacorp.

In the mid 2000s, Tod’s health diminished, but he continued composing until dementia stopped him. He died peacefully on February 27, 2015, listening to his music.

Tom Steenland wrote about his 40-year friendship with Tod in an article posted at New Music Box.