Tod Dockstader’s “organized sound” has captivated, delighted, and sometimes frightened listeners for several decades. With dozens of highly enthusiastic reviews, Starkland’s two CDs have led to the recognition of Tod Dockstader as one of the finest musique concrete composers yet to appear. The Washington Post calls Dockstader “one of the giants in the field,” while Stereophile places his output “on a par with the best.”

These two CDs, each containing over 70 minutes of strikingly original electronic music, offer significantly improved sound over the limitations of the original LPs. Dockstader carefully supervised Starkland’s transfer from his original master tapes to the final digital masters. The Washington Post notes that the extraordinary sound of the CDs “at last, is equal to the remarkable sounds Dockstader has produced.”

The booklets for these two CDs offer thorough documentation on Tod Dockstader and this music: biographical information, notes on each piece, photos, authoritative Introductions, and additional Dockstader commentary on his early influences and tortuous studio techniques. Fanfare found the booklets “gratifyingly thorough… among the best prepared I’ve seen.”

The first CD opens with Water Music. Dockstader comments:

“Water Music began with the sound of water; there is little else in the piece. I’ve described organized sound as a technique using everything and the kitchen sink; this is the piece that uses the sink – a kind of kitchen La Mer. I suspected these sound sources were capable of complex organization – in short, of making a kind of music. And yet the processes of mechanical and electronic abstraction they went through during organization did not rob them of their essential quality: a sometimes delicate, sometimes ponderous, wetness. There are six short parts, each one of varying degrees of density, acceleration, loudness. Some are lyrical, some violent – both, I feel, are qualities of water… Water Music had its premiere on WQXR in June 1963. At the end of the broadcast, the announcer stated that, since electronic music wasn’t going anywhere, the broadcast would be the last of its kind. They’d also played Stockhausen’s Gesang der Junglinge – so I went out in good company.”

is the best that I’ve heard...

never been surpassed... a masterpiece!”

This CD also presents the darkly ominous, 45-minute work many regard as Dockstader’s musique concrete masterpiece, Quatermass. The composer offers some thoughts about this extraordinary work:

“Quatermass was intended, from the start, to be a very dense, massive, even threatening, work of high levels and high energy. It was my antidote to the preceding Water Music – a work of small details, delicate textures, and some playfulness… As with all my pieces, work began with collecting what I call ‘cells’ (Schaeffer called them ‘sound objects’): hours and hours of quarter-inch tape recordings of whatever interested me, the original sound transmuted with (what are now called) ‘classical’ tape-studio techniques.”

“By the time I did Quatermass, I guess I had a library of around 300,000 feet of tape (125 hours at 15 ips). From this mass, I would select cells that seemed like they might work together into a piece, and then turn them into stereo (with more classical techniques of tape-delay and tape-echo between channels, panning, reverberation, and placement). For Quatermass, I had, for the first time, use of a three-track recorder (the third track filled the center ‘hole’ in early stereo recording), which allowed me to do more complex tape-echo rhythms than before (heard in ‘Tango’ and ‘Flight’) and thicker sound-masses – the ‘wall’ of sound I wanted for the piece.”

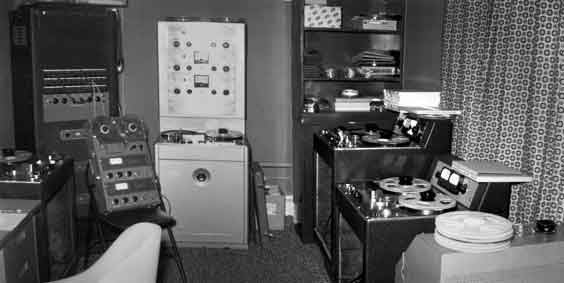

“To mix all this together, I had a six-channel mixer (tubes), one mono, one 2-track, and the 3-track machines as feeds into a quarter-inch, 2-track recorder. That was it (the most elaborate setup I ever had) – no ‘tracking,’ no sel-sync, no ‘layering,’ just one-pass mixing to the master tape. All this was tube equipment with no noise-reduction… The final (and longest) stage was to edit the mixes into the five movements. I’d guess the forty-six minutes of Quatermass were wrenched out of probably a dozen hours of mixed tape.”

“ ‘Song and Lament’ does indeed have a song and a lament. ‘Tango,’ although it doesn’t start like a tango, becomes something like a tango, and ‘Parade’ is sort of a pompous, John Philips Sousa crashing about. ‘Flight’ continues the source-ideas of ‘Tango’ on a darker level, and the final part, ‘Second Song,’ is a long working-out of the energies, and an attempt at balancing the weights, of the first four parts…”

The CD also offers Two Moons of Quatermass, unused sections from Quatermass that were heard on this CD for the first time. Dockstader writes:

“Two Moons of Quatermass were spin-offs from Quatermass: they were flung out, in the long process of editing, as outs. Later, after Quatermass was done, I went back and edited them into the Two Moons. They separated themselves from the main work because: the first Moon was too languid to work into Quatermass, and the second Moon was more playfully chaotic than Quatermass.”

meticulously composed and engineered.”

Anyone who has an interest in musique concrete and electronic music should hear this powerful, classic organized sound.

Tod Dockstader additional comments

I think I was aided, in my time and circumstances, by not having a synthesizer of any kind: no keyboards, no pre-set voices.

My “synthesizer” for everything on this CD was one or two sine-wave test generators (“oscillators” in those days) which were “played” by turning a dial. I forced them to produce harmonics (square waves) by amplifying them into distortion, and got pulse-trains out of them by temporarily rewiring them into instability (temporarily, because they had to resume life the next day as stable test generators). The “notes” they produced were achieved by editing tape, note by note (by note by note…). For Quatermass, I acquired a Heathkit test generator of my own, which I built to allow me to “switch” tones instead of having to “tune” them (like a radio). Also, when turned on or off, it made marvelous shrieks and groans.

Some composers who worked in what’s been called the “glorious junkshop” of the now-classic tape studios have looked back in awe and dismay at the amount of hard, physical work it took to make a piece. But easier isn’t necessarily better. I enjoyed it: I found it was like the best part of painting – standing on your feet all day, moving around, working with your hands, sometimes very fast, more often very slowly, mixing, cutting, stitching it together with the sound in your ears. It had a muscular joy to it. I think a lot of us had fun up on that singing high wire, teetering between control and chaos, trying to push the sound a little farther toward Something we hadn’t heard before, working in it… Listening.

Tod Dockstader

As an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota, Dockstader majored in psychology and art. Then, as a graduate student, he went on to study painting and film, paying his way by doing cartoons for local newspapers and magazines.

In 1955, Dockstader headed for Hollywood. For his first job there as an apprentice film editor, he cut picture and sound for animated cartoons, including “Mr. Magoo” and “Gerald McBoing-Boing.” He moved on to writing and storyboarding cartoons, where his greatest creation was “The FreezeYum Story,” about a Good Humor salesman who turned his ice-cream truck into a sonic spectacular, and got himself fired for his dreams. Truth following fiction, Dockstader was then laid off when the studio folded, and he moved to New York.

Becoming a self-taught sound engineer and sound effects specialist, in 1958 he apprenticed as a recording engineer at Gotham Recording. At this major commercial studio, Dockstader surreptitiously used off-work hours to collect interesting sounds and to experiment with musique concrète.

In the mid 1960s Owl Records released three albums of Dockstader’s music, which led to favorable reviews in such publications as Saturday Review, Audio and High Fidelity.

Around this time of his new national recognition, Dockstader, being an outsider without academic credentials, was denied grants and access to the major electronic music centers. (The Columbia-Princeton Center turned him away.)

In the early 1980s, interest in Dockstader was further stimulated by some highly enthusiastic reviews of the Owl recordings in alternative publications like OP, Recordings of Experimental Music, and Surface Noise.

Released in the early 1990s, Starkland’s two Dockstader CDs brought steadily increasing recognition to this pioneering composer. These CDs elicited further acclaim, from international alternative music publications like the UK’s The Wire (which praised both the music and the “obsessive care” used to produce these CDs) to mainstream US publications like The Washington Post and Stereophile (which places Dockstader alongside Varèse, Stockhausen, and Subotnick in the area of electronic music). Reinvigorated, Dockstader returned to music at the start of the 21st century, adopting computer composition in favor of tapes. New CDs appeared from Sub Rosa and ReR Megacorp.

In the mid 2000s, Tod’s health diminished, but he continued composing until dementia stopped him. He died peacefully on February 27, 2015, listening to his music.

Tom Steenland wrote about his 40-year friendship with Tod in an article posted at New Music Box.